Peter H. Davidson

Introducing: Times and Places

Reveries of time and place are recurring themes in the surrealist vocabulary of the 20th century this empowers the artist, Patricia Nix, as if by magic to take us by the hand and also by the eye down the haunting highways and byways of our collective unconscious. Our journey at an end or just beginning, we are privileged to ponder four delightful images, an aesthetic landscape of universal dimensions, all of a piece in the medium of printed collage variously entitled Leda and the Swan, Birth of Venus, Enigma, and Love Letters.

As in all art worth its keep, the artist challenges us to respond. But do we have the nerve to get into the game? If we do, the following questions must always be asked and answered: Where do we come from? Where are we going? How do we get there?

Our journey begins with Leda and the Swan. We are asked to join this winsome couple on the wing over Yonkers, of all places. Suddenly we are immobilised by the great Heron that has planted itself in infinite space before us, like some disinterested Cerberus rescues us rather languorously from the abyss. Only now do we realise that we are not alone, having been joined in our journey by Frida Kahlo and a friend who seem right at home with us in this aerial playground.

Birth of Venus. Here we are miraculously on our way again, prompted, it would seem, by some universal intelligence and driven hence by the zephyrs of Botticelli. This time our destination or quest would seem to be the same artist's haunting evocation of eternal youth or even eternal life, supremely captured, as we are reminded here, by his figure from La Primavera of an everlasting spring. Again our reveries are interrupted, sensing as before that we are in the presence of other passengers whose fate we share: a child half hidden by a harp that smiles at us inviting, and a bird of prey that sits in timeless vigilance on a rose in Magritte-like clouds just outside our window.

In Enigma, we are momentarily brought to rest before the Eternal City, fittingly our only required stop along the way. As in all great cities, real or imagined, the enticements can be both cruel and erotic. The painting of a boy on a postage stamp torments a Great Dane with a bubble never launched or felt, while a monumental head last seen in the Sistine Chapel Hoats over the city like a great tattoo that will shortly come to rest invitingly on an upturned knee. Having engaged the scrutiny of postage stamps long enough, Michelangelo's Hand of God bids us resume our journey. Lest, like the gamekeeper in the foreground surrounded by his faithful hounds, we turn into a rose and all is lost.

Finally, in Love Letters we are home again. Our journey is over and we are left to our own devices. We are back in the real world, so to speak, where time and place are joined as they are here in a kind of Victorian romp that should bring us to our senses.

Suddenly we are reminded that we are as in real life not as voyeurs, but as protagonists vitally interested in the outcome. All of the players here are interchangeably us: the man on the horse, the head behind the dome, and the caryatid in the corner, inextricably linked as if by some vast magnetic field of thought and emotion, and the letters that often bear them. These are the thoughts and emotions that leap at us from the parapet like the banshees in question or bathe together like the monumental figures in the heavens beneath the dome in a kind of cosmic consciousness.

The artist defines our world and gives it meaning, reminding us, as Patricia Nix does here, that ours is not the classic world of the Greeks, but the modern world of the Baroque where the gods, like artists, live and play among us.

Peter H. Davidson is the director of the National Arts Heritage Foundation

Introducing: Times and Places

Reveries of time and place are recurring themes in the surrealist vocabulary of the 20th century this empowers the artist, Patricia Nix, as if by magic to take us by the hand and also by the eye down the haunting highways and byways of our collective unconscious. Our journey at an end or just beginning, we are privileged to ponder four delightful images, an aesthetic landscape of universal dimensions, all of a piece in the medium of printed collage variously entitled Leda and the Swan, Birth of Venus, Enigma, and Love Letters.

As in all art worth its keep, the artist challenges us to respond. But do we have the nerve to get into the game? If we do, the following questions must always be asked and answered: Where do we come from? Where are we going? How do we get there?

Our journey begins with Leda and the Swan. We are asked to join this winsome couple on the wing over Yonkers, of all places. Suddenly we are immobilised by the great Heron that has planted itself in infinite space before us, like some disinterested Cerberus rescues us rather languorously from the abyss. Only now do we realise that we are not alone, having been joined in our journey by Frida Kahlo and a friend who seem right at home with us in this aerial playground.

Birth of Venus. Here we are miraculously on our way again, prompted, it would seem, by some universal intelligence and driven hence by the zephyrs of Botticelli. This time our destination or quest would seem to be the same artist's haunting evocation of eternal youth or even eternal life, supremely captured, as we are reminded here, by his figure from La Primavera of an everlasting spring. Again our reveries are interrupted, sensing as before that we are in the presence of other passengers whose fate we share: a child half hidden by a harp that smiles at us inviting, and a bird of prey that sits in timeless vigilance on a rose in Magritte-like clouds just outside our window.

In Enigma, we are momentarily brought to rest before the Eternal City, fittingly our only required stop along the way. As in all great cities, real or imagined, the enticements can be both cruel and erotic. The painting of a boy on a postage stamp torments a Great Dane with a bubble never launched or felt, while a monumental head last seen in the Sistine Chapel Hoats over the city like a great tattoo that will shortly come to rest invitingly on an upturned knee. Having engaged the scrutiny of postage stamps long enough, Michelangelo's Hand of God bids us resume our journey. Lest, like the gamekeeper in the foreground surrounded by his faithful hounds, we turn into a rose and all is lost.

Finally, in Love Letters we are home again. Our journey is over and we are left to our own devices. We are back in the real world, so to speak, where time and place are joined as they are here in a kind of Victorian romp that should bring us to our senses.

Suddenly we are reminded that we are as in real life not as voyeurs, but as protagonists vitally interested in the outcome. All of the players here are interchangeably us: the man on the horse, the head behind the dome, and the caryatid in the corner, inextricably linked as if by some vast magnetic field of thought and emotion, and the letters that often bear them. These are the thoughts and emotions that leap at us from the parapet like the banshees in question or bathe together like the monumental figures in the heavens beneath the dome in a kind of cosmic consciousness.

The artist defines our world and gives it meaning, reminding us, as Patricia Nix does here, that ours is not the classic world of the Greeks, but the modern world of the Baroque where the gods, like artists, live and play among us.

Peter H. Davidson is the director of the National Arts Heritage Foundation

-

Patricia Nix, Chesapeake Bay Annunciation, 2015

Patricia Nix, Chesapeake Bay Annunciation, 2015 -

Patricia Nix, Eve's Orange, 1992

Patricia Nix, Eve's Orange, 1992 -

Patricia Nix, Baptism, 1991

Patricia Nix, Baptism, 1991 -

Patricia Nix, Dominoes, 1988

Patricia Nix, Dominoes, 1988 -

Patricia Nix, Circus

Patricia Nix, Circus -

Patricia Nix, Eve's Apple

Patricia Nix, Eve's Apple -

Patrica Nix, Evening Star

Patrica Nix, Evening Star -

Patrica Nix, Leda and the Swan

Patrica Nix, Leda and the Swan -

Patricia Nix, People With Heads are Rare

Patricia Nix, People With Heads are Rare -

Patrica Nix, St Sebastian

Patrica Nix, St Sebastian -

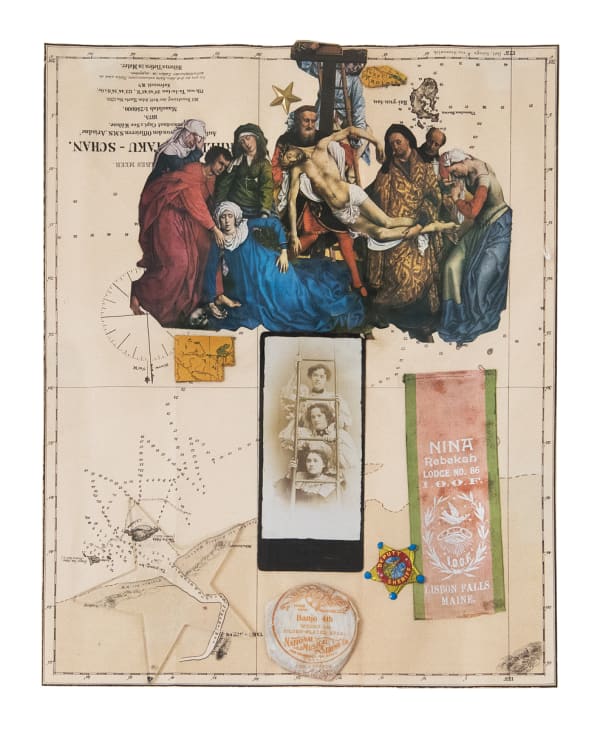

Patrica Nix, The Night Uncle Aubrey Met Jesus

Patrica Nix, The Night Uncle Aubrey Met Jesus -

Patricia Nix, Woman With Poinsetta

Patricia Nix, Woman With Poinsetta